CORPORATE SOUL: Jan Berry’s Quest for Business Autonomy in 1966

By Mark A. Moore

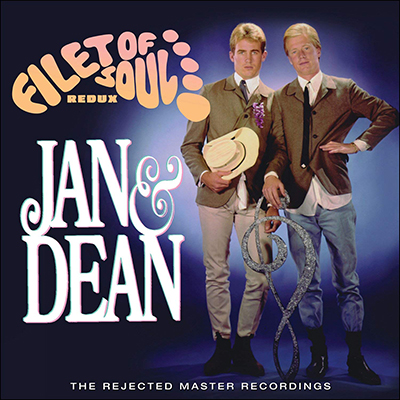

Author of Dead Man’s Curve: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Life of Jan Berry

In the wake of Jan Berry’s horrific 1966 car accident, Dean Torrence first sprang the sound collage strangeness of Filet of Soul on the record-buying public in 1971 when he plopped an abridged version on Side 4 of Anthology—without explaining what it was. Even without context legendary Rock journalist Dave Marsh proclaimed it “an almost operatic excursion through the blackest rock and roll humor ever waxed.” Following the Anthology experiment the master recordings rejected by Liberty Records in ‘66 remained in Dean’s sole—soul—possession, and over the years poor quality bootlegs made the rounds among collectors. The September 2017 release of Filet of Soul Redux warrants a closer look at Jan’s career in late ’65 and early ’66 to provide crucial context not found in the brief liner notes penned by Dean Torrrence and David Beard.

To set the stage, Jan—the creative and technical force behind the duo—was a staff songwriter and record producer for Screen Gems-Columbia Music, a major entertainment corporation based in New York City. Jan had first signed in these capacities with Nevins-Kirshner Associates in September 1961. When Nevins-Kirshner was acquired by Screen Gems in April of ‘63, Jan signed three new lucrative contracts with the company as a songwriter, record producer, and as the artist Jan & Dean. At that point he took full control and became responsible for delivering the duo’s creative product.

The West Coast office of Screen Gems—based at 6515 Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood—was the California extension of the Brill Building. The office was run by Lou Adler from 1961 until he was fired for breach of contract in 1964. Adler had been Jan & Dean’s manager since their beginning in 1959. Lou was hired to work exclusively on behalf of Nevins-Kirshner and later Screen Gems, but ran afoul of the company when he violated the terms of his agreement to establish Trousdale Music and Dunhill Productions. After the separation Adler’s Dunhill office, with partners Pierre Cossette and Bobby Roberts, continued to manage Jan & Dean. Jan remained employed by Screen Gems, but it was the Dunhill team that got Jan & Dean their film and television projects with Paramount and 20th Century-Fox in 1965.

By ‘65 the string of hit records co-written, arranged, and produced by Jan had put Jan & Dean in the upper echelon of their peers. While Jan had achieved major success with Screen Gems, however, he felt more and more constrained by the corporate atmosphere. He answered directly to executives in New York and there were rigid quotas, deadlines, and procedures. It would have been a full-time job for anyone but Jan happened to be juggling his time between medical school and music. None of his peers operated in such a demanding dual environment. He essentially gave half of his time to both of those endeavors. The balancing act spoke volumes of his extraordinary intellect and skill, but the frenetic pace had begun to wear upon him. Since the beginning of his career with Jan & Arnie in 1958, Jan had thrived on doing things his own way while bending establishment rules as far as possible. Now he longed for complete professional independence and his first step in that direction was the establishment of his own production company, Berry Enterprises Ltd., in August 1965. He launched the firm with his own money and began exploring his professional options.

By late ’65 when the Filet of Soul concerts were committed to tape, backed by members of the Wrecking Crew, Jan had further charted his course toward independence with plans to establish his own record label. His corporate relationship with Screen Gems, however, would continually thwart his attempts at autonomy. He was contractually bound to the company. All of the material he wrote and recorded for Jan & Dean or other artists was owned exclusively by Screen Gems—both the publishing and the master recordings. He owed them material, and in return they paid him a lot of money to deliver product. How could he break away? The question consumed him and he became increasingly frustrated.

In the middle of Jan’s corporate tug-of-war was Liberty Records. Established in 1955, Liberty was a Hollywood success story, an independent label that scored major hits with well-known artists. However, the duo had not signed with Liberty on their own. Their label contract was first brokered by Nevins-Kirshner in late 1961 and then renewed and revised by Screen Gems in ’63. While the duo undersigned the contracts, the relationship with Liberty was managed by Jan’s corporate bosses back East. Liberty essentially paid Screen Gems a royalty for the privilege of recording and distributing Jan & Dean’s music. Jan worked closely with the label but he answered to Don Kirshner in New York. In short, Screen Gems owned Jan Berry and Jan & Dean—lock, stock, and barrel.

By mid-1964 Jan butted heads regularly with executives at Liberty and Screen Gems, questioning the label’s accounting practices and a host of other issues. Jan’s astute lawyer Gunther Schiff sparred often with veteran corporate attorneys for the mother company led by Irwin Z. Robinson and David Horowitz. The New York boys were tough but always willing to negotiate to get everyone on the same page. They played hardball and they played to win. Schiff scored some important concessions for Jan, but in the long run the corporation always won. And that was the main motivating factor in Jan’s push for business independence.

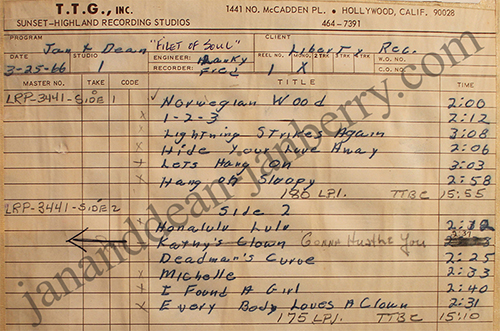

When he began assembling Filet of Soul in late ‘65 and early ‘66 the sessions devolved into a subversive, sound effects laden figurative middle finger to the establishment, complete with expletives written by Jan on the acetate disc labels. “Dean would like to do his virgin . . . uh, version of ‘Michele’,” quipped Jan during a recorded show . He kept a hopeful eye toward March 31, 1966, the date the Liberty contract would officially end, but he would ultimately be disappointed.

Screen Gems had recently exercised its option to renew Jan’s songwriting, production, and artist contracts for another three years through 1969, and they fully expected Jan to do his part toward securing a label for the duo’s future music—whether it was a renewed agreement with Liberty or another label altogether. But the deal breaker for Jan was the fact that he was not allowed to have a personal financial stake in any such future label or company. That automatically ruled out Berry Enterprises and Jan’s fledgling J&D Records.

With his frustration level at an all-time high, Jan walked away from negotiations with the company. Yet their terms were more than reasonable. They were willing to let Jan score a deal on his own with a label of his choosing. Barring that they offered to find a new label on their end, subject to Jan’s approval. Company executives wanted Jan to come to Manhattan for a meeting on how to proceed, but they were also willing to fly to California to meet on Jan’s turf. But he was so dead set on launching his own companies—a nonstarter from a contractual standpoint—he avoided contact altogether. Screen Gems admonished Jan for having an “intransigent attitude” and “acting at variance to his own best interests.” They also threatened to put Jan & Dean’s recording career on hiatus and had the power to do so. They threatened to seek damages but Jan in turn threatened to countersue. Unfortunately for Jan, he didn’t have a legal leg to stand on. He was stuck until Screen Gems exercised all of its options on his contracts. But this contentious exchange revealed that the company still considered Jan & Dean a viable commercial act in 1966, and fully expected to secure another record deal for the duo. In their view Jan & Dean were not finished in March of ’66. It was simply time for a new label.

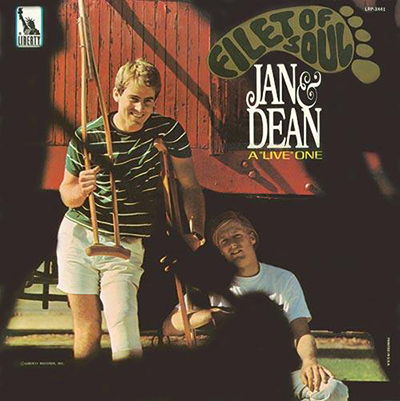

As initially submitted, Filet of Soul would likely have given pause to any commercial record company in 1966. Liberty had the discretion to reject the material and did so. Meanwhile, since Jan couldn’t use Berry Enterprises to record music, he used the firm to book what turned out to be Jan & Dean’s final concert appearances in the South and Midwest in March and April of ’66.

While Jan stepped away Liberty assembled the album master for what became the released version of Filet of Soul on March 25, 1966, overseen by A&R executive Dave Pell. With the album in the can, however, they sat on it for the next month. Citing the pending end of Jan & Dean’s contract, Liberty also initially refused to release the latest single Jan had submitted, a cover of the Beatles’ non-single album cut “Norwegian Wood.” Jan had written a deep arrangement for the song and had spent a lot of time working on it in the studio. He felt so strongly about it that he offered to purchase the master for use on another label.

And that is where matters stood on April 12, 1966, when Jan Berry skidded into Rock mythology near Dead Man’s Curve.

With Jan in a state of semi-consciousness at UCLA Medical Center, Liberty released its version of Filet of Soul on April 25. The album spent a modest five weeks on the charts, peaking at #127 on Billboard. Following pressure from attorney Gunther Schiff, the label finally issued the single “Norwegian Wood” backed with “Popsicle” on May 3. Jan had begun revisiting “Popsicle”—which dated from 1963—in the studio as early as July 1965. A take of “Popsicle Man” had been revisited by Dave Pell on March 25 at the time Liberty’s version of Filet of Soul was assembled. On May 12 Schiff noted: “The new single, ‘Norwegian Wood’ b/w ‘Popsicle,’ has been released. The latter was a tape which Liberty had unreleased and which they liked better than the suggested other side. Phil [Skaff] tells me that all the indicators point to a hit record on the single, with the emphasis being on ‘Popsicle.’” The single peaked at #21 on Billboard and #24 on Cash Box, spending more than two months on the charts.

Jan faced a long and painful road toward recovery. He was discharged from the hospital in mid-June and transferred to the rehabilitation facility at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. He began learning to walk and talk again. One year to the month after suffering brain damage and partial paralysis, Jan returned to the studio in April 1967 to begin recording new music for what became Carnival of Sound.

Life can have a higher meaning.

To learn more about Jan Berry and Jan & Dean, purchase Dead Man’s Curve: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Life of Jan Berry.

BUY THE ALBUM:

Filet of Soul Redux: The Rejected Master Recordings

Jan & Dean

Omnivore OVDG-226

© 2017 Mark A. Moore. All rights reserved.

Follow in Social Media:

More Stories

Some Things You Never Forget!

Shades of Cool — An In-Depth Interview with Author Mark A. Moore

Carnival of Sound